For example, I was looking at the immigration arrival record of Gerhard Fast #117515 (ABT 1774-1830) who moved to Russia in 1819. Here's the translation of that record from the book:

| Peter Rempel, Mennonite Migration to Russia, 1788-1828 (Winnipeg, Manitoba Mennonite Historical Society, 2000) 168 |

Next, they had no cash and no horses, which means that they probably walked the roughly nine hundred miles and carried their few possessions on their backs or in a hand cart. They had to be tough and determined to make such a long journey on foot. Or perhaps, they rode on the wagon of friends or relatives who were in their group of immigrants. That also means that they were dependent on subsidies from the Russian government to eat along the way and to start their new farm in Russia.

Finally, they had household possessions worth 129 rubles. There's no way to convert rubles from that time period to current dollars, so that number alone doesn't mean much. But Peter Rempel gave source citations for all his translations. In this case, it comes from list "W4," and if you look at the back of his book, he gives the original source for all his translations.

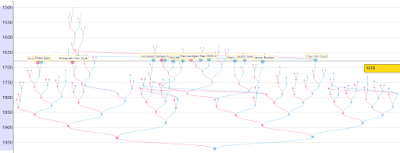

He deposited a microfilm with all his original sources at the Mennonite Historical Centre Archive in Winnipeg, and I got a copy of the original. Here is the snippet of Gerhard Fast's arrival record:

Here is what the columns mean:

Family #80

Head of household - Gergard" Fast"

1 male (Gerhard)

2 females (wife Helena Wiebe and daughter Katharina)

3 total people

no cash

no horses

household possessions worth 129 rubles

total possessions worth 129 rubles (i.e. including cash, horses, and household possessions)

There were 177 families listed in this document, and the clerk totaled the value of all their possessions at the end, so we can figure out the average that each family had. Perhaps this group was unusually wealthy or unusually poor - we don't know. But we can see where Gerhard and his family fit in the group.

Recall that first three columns list the number of males, females, and total people. The fourth column is the cash they brought, which totaled 113,615 rubles for 177 families, or an average of 642 rubles per family. Gerhard had no cash, so he was definitely among the poorer in the group.

The next column is the horses, which were worth 9036 rubles (the document doesn't tell us the number of horses, just their value), which would be an average of 51-rubles-worth of horses per family.

Then the household possessions are totaled at 47,814 rubles, or an average of 270 rubles per family. Gerhard's family had 129 rubles, so they had less than half the average.

The final column is the value of total possessions, which is 172,462 rubles, or an average of 974 rubles per family. Again Gerhard had only 129 rubles worth of total possessions.

In all the economic measures in the immigration report, Gerhard and Helena Fast were definitely poor. They weren't the poorest because there were families who came with literally nothing. But they were close to the bottom.

This context tells us a lot about Gerhard's family. They must have come from real poverty in Prussia, walked to the Molotschna colony in Russia and were given a farm in the Rudnerweide village. They would have had a lot of work to build their farm in Russia into a viable economic unit. But you can understand why a poor family from West Prussia would be willing to undertake such a difficult journey. Not only did immigration give them the opportunity to practice their faith in Russia without the restrictions that Prussia put on the Mennonites, but also it gave them a chance to escape grinding poverty. Perhaps their poverty back in West Prussia even explains why their first four children died young. This was truly a new beginning.

Whenever you come across records with areas of land or amounts of money, try to put them in context. If you can find the totals for the village or the group of immigrants, then you can compare them to the average. The principle applies to any kind of records, even to more recent property tax records from the US. Thus you can give context to the lives of your ancestors.