In Part I of this series, we explained how to search the German war records called EWZ for Mennonites. Hopefully you have gotten one or more files that interested you. Now we'll dive into the files.

The files generally contain three types of documents. The first one gives the personal details of the applicant. Below we are looking at the file of Katharina (Fast) Warkentin, who was the actual applicant for citizenship in the Jakob Fast file that I mentioned in part I.

Immediately following on the page is the information about her parents:

This gives her parents' names, birth places, birth dates, death dates, and religion (Mennonite). If we compare to GM, we see that her father Jakob Fast's birth date there is 7 Nov 1867, which makes more sense than 1887, since he would have been only 14 years old when she was born in 1901 if he were born in 1887.

But it gets better. The next information is her grandparents' names.

Her paternal grandfather was Klaus Fast, and this information is not in GM, so we should submit it as a correction. The main record database from this time period for Molotschna colony is the school records, so let's search those for a father Klaas Fast and a son Jacob Fast, using the index compiled by Tim Janzen.

In the 1873-1874 school records, we find a Klaas Fast in Ladekopp, and he has two daughters Helena (b. ABT 1863) and Eva (b. ABT 1865). This is probably the same family, but our Jacob is likely just a year too young to be attending school. Unfortunately, the family is not listed in any of the other school records, and I can't find Helena or Eva in GM.

I'm going to submit this information to GM as a correction.

The next question is who were Klaas Fast's parents. I have a good candidate, but I haven't found sufficiently strong evidence yet, so that will (hopefully) be the subject of a future post.

I hope these two posts have given you a sense of the value of the EWZ records, how they can be used to research Soviet-era Mennonites, and how they can be combined with earlier records to research imperial-era Mennonites as well.

Tuesday, January 24, 2017

Sunday, January 22, 2017

Using German War Records (Part I)

During World War II, the German occupied large parts of Europe, including the area of the Soviet Union where many Mennonite lived. They attempted to document the ethnicity of all Germans in occupied territory in order to grant them German citizenship. To accomplish this task, they collected family trees and life stories of all the ethnic Germans in German-controlled areas. The United States Army seized these records in 1945 at the end of the war and transferred them to the National Archives. Eventually the records were microfilmed and returned to Germany. Since then individuals have purchased many microfilms and donated them to various genealogy research centers, where they have been indexed. The indexes are online and can be searched, so this is an incredibly valuable record. They are called EWZ records, short for Einwandererzentalstelle or Central Immigrant Office.

There are a few caveats in order. First, applicants were attempting to prove German ethnicity so that they could receive citizenship from the occupying power, so they certainly had an incentive to shade the truth in some situations. Second, these documents were collected under wartime conditions and many church and family records had been destroyed first by Soviet repression and then by the vagaries of war. Sometimes people were recalling details from memory. Third, many Mennonites had been arrested or scattered before World War II and more were deported to Kazakstan in 1941 by the Soviets - since these were not in German-occupied territory, they did not apply for German citizenship during the war. Finally, not all microfilms with Mennonites have been purchased from the National Archives and donated to research centers and not all donated microfilms have been indexed. Despite these very real limitations, this is a fantastic research collection.

It takes a bit of knowledge to find the information you want. The place to start is the Odessa3 online library's search page. At the top of the page is Searching the Odessa Library. Enter your surname of interest or village name as the Query String. Make sure to select War Records as the Data Category. I put in "Fast" as an example below.

You'll get a LONG list of results that starts something like this:

On this page, you'll want to click on CTRL-F to open a search box in your browser and then type in a given name or a village or some other keyword to search. In this case I'm trying to find out if there are descendants of Gerhard Gerhard Fast #45022 (b. ABT 1767) of Ladekopp in the database, so I enter Ladekopp as the search term. Of course, he was no longer alive by the 1940s, but perhaps some of his descendants who applied for German citizen during World War II (or their parents or grandparents) were born in Ladekopp. I found a number of results, but here is one that looks promising:

I've marked Jakob Fast in red. The index gives his birth date of 7 Nov 1887 and village of Ladekopp. Then it gives a file number of A3342 EWZ50-I088 and frame number 0558. Notice that listed next is a Sara Fast whose maiden name was Nickel with the same file and frame numbers - she might be his wife. Note the file and frame numbers because you will need them to order copies.

To order the files, there are a couple places that have the most. The Mennonite Historical Society of British Columbia has undertaken a massive project to scan many of the films, so they are a good placed to start. Plus they only charge 0.10 CAD per page. The Germans from Russia Heritage Society (whose index is on the Odessa3 page that we used) also has many films, but they charge 2.00 USD per page. The files generally run 10-30 pages, so it can add up if you are getting several files.

Now you should know how to search the indices. The next post will explain how to use the documents in the file that you will receive.

There are a few caveats in order. First, applicants were attempting to prove German ethnicity so that they could receive citizenship from the occupying power, so they certainly had an incentive to shade the truth in some situations. Second, these documents were collected under wartime conditions and many church and family records had been destroyed first by Soviet repression and then by the vagaries of war. Sometimes people were recalling details from memory. Third, many Mennonites had been arrested or scattered before World War II and more were deported to Kazakstan in 1941 by the Soviets - since these were not in German-occupied territory, they did not apply for German citizenship during the war. Finally, not all microfilms with Mennonites have been purchased from the National Archives and donated to research centers and not all donated microfilms have been indexed. Despite these very real limitations, this is a fantastic research collection.

It takes a bit of knowledge to find the information you want. The place to start is the Odessa3 online library's search page. At the top of the page is Searching the Odessa Library. Enter your surname of interest or village name as the Query String. Make sure to select War Records as the Data Category. I put in "Fast" as an example below.

You'll get a LONG list of results that starts something like this:

On this page, you'll want to click on CTRL-F to open a search box in your browser and then type in a given name or a village or some other keyword to search. In this case I'm trying to find out if there are descendants of Gerhard Gerhard Fast #45022 (b. ABT 1767) of Ladekopp in the database, so I enter Ladekopp as the search term. Of course, he was no longer alive by the 1940s, but perhaps some of his descendants who applied for German citizen during World War II (or their parents or grandparents) were born in Ladekopp. I found a number of results, but here is one that looks promising:

I've marked Jakob Fast in red. The index gives his birth date of 7 Nov 1887 and village of Ladekopp. Then it gives a file number of A3342 EWZ50-I088 and frame number 0558. Notice that listed next is a Sara Fast whose maiden name was Nickel with the same file and frame numbers - she might be his wife. Note the file and frame numbers because you will need them to order copies.

To order the files, there are a couple places that have the most. The Mennonite Historical Society of British Columbia has undertaken a massive project to scan many of the films, so they are a good placed to start. Plus they only charge 0.10 CAD per page. The Germans from Russia Heritage Society (whose index is on the Odessa3 page that we used) also has many films, but they charge 2.00 USD per page. The files generally run 10-30 pages, so it can add up if you are getting several files.

Now you should know how to search the indices. The next post will explain how to use the documents in the file that you will receive.

Saturday, January 21, 2017

The Battle of the Grandmas

No, I'm not talking about a nasty cage fight between inlaws or even a spat between Nana and Grammy at the Christmas dinner table after too much eggnog. I'm talking about the Grandma (Genealogical Registry and Database of Mennonite Ancestry) database, and which version is best for you.

What is Grandma? It contains the genealogical information on 1.3 million Low-German Mennonites from the 1400s to the present. It is maintained by the California Mennonite Historical Society and consists of lightly-curated submissions from users.

If you're not using Grandma (or GM), you are missing out. It's the quickest way to access the research results of most Mennonite genealogists; and since most researchers provide their sources, you can get good ideas for extending your own research. And it's amazingly current - I was surprised to find myself in the database when I opened it (I'm #112822).

There are two versions - an online database and a CD/downloadable database. Which one should you use?

Let's start with the CD/download ($40 with two years of data updates). Here's a screenshot of my great-great-grandfather Jacob Fast. Not all of this information came with the database as I have added from my own research.

The GM database works with any software, but since GM is most commonly used with the shareware Brother's Keeper (BK), I'll make some comments about it as well.

Database

1. More events and facts - The online database only has birth, baptism, marriage, death, burial, and immigration. But there are many more pieces of information on the CD/download such as residence, census, physical description, church membership, naturalization, probate, cause of death, and much more.

2. Control of the data - You can manage the data - extracting a subset for a project, merging it with non-Mennonite relatives not in GM, make instant changes, do things that the committee running GM disagrees with, export GEDcoms to post online, etc. But most importantly, you can instantly edit your own data.

3. Fuller source citations and notes - The sources online are quite abbreviated

4. Includes full data on living people

BK Software

1. Many more report options and some more customization than the online version, although not as much as Legacy.

2. Clean, intuitive layout with separate tabs for children, siblings, notes, to-do, etc. that make them instantly accessible without cluttering the screen.

3. Search results box has more info than the online version, so it's easier to see if you found the person you want.

4. BK is faster than Legacy at handling a database with 1.3 million people.

And now for the online ($20 for two years of access) version. First, a screenshot for the same Jacob Fast:

1. Very limited export of data - I think an Ahnentafel report of a person's ancestor is the only export. No GEDcoms.

2. No editing - Unless you just want to view things, you'll have to do your own work in your own genealogy software or on paper.

3. Innovative searches with date ranges, locations for vital events, keywords in immigration data, pair searches for husband-wife, parent-child, and siblings. Although BK has many more searches, they don't have the pair searches, and the searches in BK are so cotton-pickin' sloooooooow. To me this is worth the price of online access by itself.

4. Requires internet access.

5. Easy to submit corrections and new information with a button on each person's page. With the download version, you have to e-mail the information.

6. Deals with the name-spelling problem automatically. What if you are looking for Aganetha Klassen? The spelling possibilities are endless - Agnetha, Agneta, Agnete, Agnes, Aganeta, etc. etc. And then the last name - Klassen, Klaassen, Klaasen, Claassen, Classen, Classin, etc. etc. First and last names are coded when they are entered into the database - with the online database, you never have to worry about this. But in the downloadable database, they have added a "reference code" for each name combination as a workaround. So you would have to search for /036ag if you wanted all the variations of Aganetha Klassen on the CD. And you would need to remember to add the reference code to any new people whom you enter.

So what's my recommendation?

If you're a serious genealogist, get both. You need a database you can edit and print reports from (the download version) and the excellent searches and name-handling capabilities of the online database.

If you're not going to get both, then I think it comes down to whether you value the editing and report functions. If you're content just looking things up in the database and printing the most basic reports, then the cheaper online version is for you. Otherwise, get the download/CD.

What is Grandma? It contains the genealogical information on 1.3 million Low-German Mennonites from the 1400s to the present. It is maintained by the California Mennonite Historical Society and consists of lightly-curated submissions from users.

If you're not using Grandma (or GM), you are missing out. It's the quickest way to access the research results of most Mennonite genealogists; and since most researchers provide their sources, you can get good ideas for extending your own research. And it's amazingly current - I was surprised to find myself in the database when I opened it (I'm #112822).

There are two versions - an online database and a CD/downloadable database. Which one should you use?

Let's start with the CD/download ($40 with two years of data updates). Here's a screenshot of my great-great-grandfather Jacob Fast. Not all of this information came with the database as I have added from my own research.

The GM database works with any software, but since GM is most commonly used with the shareware Brother's Keeper (BK), I'll make some comments about it as well.

Database

1. More events and facts - The online database only has birth, baptism, marriage, death, burial, and immigration. But there are many more pieces of information on the CD/download such as residence, census, physical description, church membership, naturalization, probate, cause of death, and much more.

2. Control of the data - You can manage the data - extracting a subset for a project, merging it with non-Mennonite relatives not in GM, make instant changes, do things that the committee running GM disagrees with, export GEDcoms to post online, etc. But most importantly, you can instantly edit your own data.

3. Fuller source citations and notes - The sources online are quite abbreviated

4. Includes full data on living people

BK Software

1. Many more report options and some more customization than the online version, although not as much as Legacy.

2. Clean, intuitive layout with separate tabs for children, siblings, notes, to-do, etc. that make them instantly accessible without cluttering the screen.

3. Search results box has more info than the online version, so it's easier to see if you found the person you want.

4. BK is faster than Legacy at handling a database with 1.3 million people.

And now for the online ($20 for two years of access) version. First, a screenshot for the same Jacob Fast:

1. Very limited export of data - I think an Ahnentafel report of a person's ancestor is the only export. No GEDcoms.

2. No editing - Unless you just want to view things, you'll have to do your own work in your own genealogy software or on paper.

3. Innovative searches with date ranges, locations for vital events, keywords in immigration data, pair searches for husband-wife, parent-child, and siblings. Although BK has many more searches, they don't have the pair searches, and the searches in BK are so cotton-pickin' sloooooooow. To me this is worth the price of online access by itself.

4. Requires internet access.

5. Easy to submit corrections and new information with a button on each person's page. With the download version, you have to e-mail the information.

6. Deals with the name-spelling problem automatically. What if you are looking for Aganetha Klassen? The spelling possibilities are endless - Agnetha, Agneta, Agnete, Agnes, Aganeta, etc. etc. And then the last name - Klassen, Klaassen, Klaasen, Claassen, Classen, Classin, etc. etc. First and last names are coded when they are entered into the database - with the online database, you never have to worry about this. But in the downloadable database, they have added a "reference code" for each name combination as a workaround. So you would have to search for /036ag if you wanted all the variations of Aganetha Klassen on the CD. And you would need to remember to add the reference code to any new people whom you enter.

So what's my recommendation?

If you're a serious genealogist, get both. You need a database you can edit and print reports from (the download version) and the excellent searches and name-handling capabilities of the online database.

If you're not going to get both, then I think it comes down to whether you value the editing and report functions. If you're content just looking things up in the database and printing the most basic reports, then the cheaper online version is for you. Otherwise, get the download/CD.

Nebraska Gives Me a "Yes" and a "No"

A few weeks ago, I did a project to see which vital records I had and which ones I needed to order. I wrote a post about it here. In that project, I realized that both my great-great-grandparents Fast, Jacob Fast #35385 (1831-1905) and Elisabeth (Thiessen) Fast #35386 (1832-1912) had died after Nebraska started to require death certificates to be filed with the state. So I sent a request and $16 each to the vital records section. A few days ago my answer came in the mail with a "yes" and a "no."

Let's begin with the "no." Nebraska started to require death certificates in 1904, and Jacob Fast died in February 1905, so a record should have been filed with the state. However, the state web site warns that it took some time before the law was generally complied with. I imagine that compliance was poorer in rural areas and those farther from Omaha and Lincoln. Jacob Fast died near Jansen, a village in southeastern Nebraska. So I was disappointed but not terribly surprised to get a "no" from the state - all indices had been searched but no death certificate for Jacob Fast was found.

Of course, the state kept my $16 because you are paying for the search not the certificate. But it's a risk you have to take if you want to get any records from the state.

But I had better luck and a "yes" for his wife and my great-great-grandmother, Elisabeth (Thiessen) Fast, who died in 1912. Her death certificate didn't reveal any new information other than her burial date (12 July 1912), but it did confirm her death date (10 July 1912), place of death (Cub Creek Township, Jefferson County, Nebraska), and her parents' names (David Thiessen and Elisabeth Franz). I knew these latter three pieces of information from obituaries and family histories, but it's nice to get a government document that confirms them.

Perhaps the most interesting thing was the doctor's note about cause of death, "Did not attend deceased. Was called and patient died before I arrived. Death undoubtedly from natural causes. Never saw deceased alive." Even though she died at age 80, she might have never been to the doctor, certainly not in the last few years of her life. Her obituary in the Mennonitische Rundschau (28 August 1912, p. 8) says that she had experienced chest pains in the couple days before she died but she insisted on going to visit her other children and grandchildren anyway and then died of a heart attack. She must have been one tough lady.

|

| Jacob and Elisabeth Fast and their daughter Katharina. Probably taken in the mid- to late-1890s. |

Let's begin with the "no." Nebraska started to require death certificates in 1904, and Jacob Fast died in February 1905, so a record should have been filed with the state. However, the state web site warns that it took some time before the law was generally complied with. I imagine that compliance was poorer in rural areas and those farther from Omaha and Lincoln. Jacob Fast died near Jansen, a village in southeastern Nebraska. So I was disappointed but not terribly surprised to get a "no" from the state - all indices had been searched but no death certificate for Jacob Fast was found.

Of course, the state kept my $16 because you are paying for the search not the certificate. But it's a risk you have to take if you want to get any records from the state.

|

| Jacob Fast, died 24 February 1905, no death certificate found, Health Records Management Section, State of Nebraska, Lincoln, Nebraska, searched 5 January 2017. |

But I had better luck and a "yes" for his wife and my great-great-grandmother, Elisabeth (Thiessen) Fast, who died in 1912. Her death certificate didn't reveal any new information other than her burial date (12 July 1912), but it did confirm her death date (10 July 1912), place of death (Cub Creek Township, Jefferson County, Nebraska), and her parents' names (David Thiessen and Elisabeth Franz). I knew these latter three pieces of information from obituaries and family histories, but it's nice to get a government document that confirms them.

|

| Elizabeth Fast death certificate, died 10 July 1912, dated 11 July 1912, #6027, Vital Records Office, Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services, Lincoln, Nebraska. |

Perhaps the most interesting thing was the doctor's note about cause of death, "Did not attend deceased. Was called and patient died before I arrived. Death undoubtedly from natural causes. Never saw deceased alive." Even though she died at age 80, she might have never been to the doctor, certainly not in the last few years of her life. Her obituary in the Mennonitische Rundschau (28 August 1912, p. 8) says that she had experienced chest pains in the couple days before she died but she insisted on going to visit her other children and grandchildren anyway and then died of a heart attack. She must have been one tough lady.

Saturday, January 14, 2017

From Rust and Yellow Paint to Granite

In a previous post, I described how my aunt and I had put a marker at the grave of my great-great-grandfather on my dad's side, Johann Sudermann. Here's the story of the second grave marker that I helped put up.

My maternal grandfather Cornelius K. Siemens had two wives, Katharina J. K. Plett #49147 (1889-1920) and Margaretha H. Reimer #321744 (1895-1993). Not at the same time, of course - his first wife died of breast cancer in 1920. When he remarried in 1930, he and his four children moved from Manitoba to Kansas. At family reunions in Manitoba, we have gone to Katharina's grave at Riverside (formerly Rosenhoff) a couple times, and it was poorly marked.

You can't read it in the picture, but if you looked at the right angle, you could see that it said, "Mrs. C. K. Siemens" in faint yellow paint. This marker was obviously not going to last much longer. Even though she wasn't technically my grandmother (my grandmother was Margaret, his second wife), she was the grandmother of my older cousins, to whom I am very close. And she played a large role in my grandfather's life and that of my older uncles and aunts. So I didn't want her grave to be lost.

I organized a family project to raise money for a tombstone, and we collected enough and placed a tombstone at her grave. As a genealogist, I insisted that we put her first and maiden names on the tombstone, even though the original marker followed the tradition at the time she died and just called her "Mrs. C. K. Siemens." We kept the spirit of the original marker by prefacing her name with "Mrs. C. K." because that is how she would have been called back then. Even though she died almost a century ago, Grandmother Katie's memory will not be lost.

My maternal grandfather Cornelius K. Siemens had two wives, Katharina J. K. Plett #49147 (1889-1920) and Margaretha H. Reimer #321744 (1895-1993). Not at the same time, of course - his first wife died of breast cancer in 1920. When he remarried in 1930, he and his four children moved from Manitoba to Kansas. At family reunions in Manitoba, we have gone to Katharina's grave at Riverside (formerly Rosenhoff) a couple times, and it was poorly marked.

|

| Mrs. C. K. Siemens tombstone, Rosenhoff Cemetery, Riverside, Manitoba, 27086 Road 2E, on west side of road, 3rd row from west, 3rd grave from south, photograph by Steve Fast, 28 July 2014. |

You can't read it in the picture, but if you looked at the right angle, you could see that it said, "Mrs. C. K. Siemens" in faint yellow paint. This marker was obviously not going to last much longer. Even though she wasn't technically my grandmother (my grandmother was Margaret, his second wife), she was the grandmother of my older cousins, to whom I am very close. And she played a large role in my grandfather's life and that of my older uncles and aunts. So I didn't want her grave to be lost.

I organized a family project to raise money for a tombstone, and we collected enough and placed a tombstone at her grave. As a genealogist, I insisted that we put her first and maiden names on the tombstone, even though the original marker followed the tradition at the time she died and just called her "Mrs. C. K. Siemens." We kept the spirit of the original marker by prefacing her name with "Mrs. C. K." because that is how she would have been called back then. Even though she died almost a century ago, Grandmother Katie's memory will not be lost.

Mistakes in the 1835 Molotschna Census

When you are using the 1835 Molotschna census, you should always confirm the entries by looking at the original. I have been told that the translators of the English version had only a poor microfilm copy to work from, so they had a difficult time reading it. Now much better copies are available.

Here is an example I just found. I was looking at Abraham Kornelius Fast, who lived at Sparrau #22 in the census. His entry says that he transferred from the Neukirch village (underlined in red) in 1830.

Since all males who lived in a village after the previous census in 1816 are listed in that village, even if they had moved away or died, I could look at his entry in Neukirch, and it should show that he moved to Sparrau. I looked in the index, and there was no Abraham Fast in Neukirch. So I thought that maybe he had been missed in the index. So I went through the English translation of the census for Neukirch page by page. Again, nothing.

Then I checked the original Russian for Neukirch village, and I found him at Neukirch #23. "Abraham Korneliusov Fast" is underlined in blue and "Sparrau" in red.

What had happened? Why wasn't he in the English? When at looked at the English translation for Neukirch #23, he was there; but the name was mistranslated at Voth not Fast. This is an easy mistake to make because Voth in Russian is Фотъ while Fast in Russian is Фасть. The two names look quite similar in Russian, and if you're dealing with a poor microfilm copy. . . .

[A sharp-eyed reader might notice that the Sparrau entry says he moved to that village in 1830 while the Neukirch entry says that he moved away from that village in 1833. That discrepancy is in the original. It may have arisen because people often physically moved from one village to another but it took time for their legal registration to be transferred.]

Here is an example I just found. I was looking at Abraham Kornelius Fast, who lived at Sparrau #22 in the census. His entry says that he transferred from the Neukirch village (underlined in red) in 1830.

Then I checked the original Russian for Neukirch village, and I found him at Neukirch #23. "Abraham Korneliusov Fast" is underlined in blue and "Sparrau" in red.

What had happened? Why wasn't he in the English? When at looked at the English translation for Neukirch #23, he was there; but the name was mistranslated at Voth not Fast. This is an easy mistake to make because Voth in Russian is Фотъ while Fast in Russian is Фасть. The two names look quite similar in Russian, and if you're dealing with a poor microfilm copy. . . .

[A sharp-eyed reader might notice that the Sparrau entry says he moved to that village in 1830 while the Neukirch entry says that he moved away from that village in 1833. That discrepancy is in the original. It may have arisen because people often physically moved from one village to another but it took time for their legal registration to be transferred.]

Tuesday, January 10, 2017

Can you figure out this date?

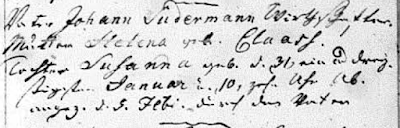

Take a look at this birth record of Susanna Sudermann, daughter of Johann Sudermann, from the Neuteich Lutheran parish's register of Mennonite births in 1819 in West Prussia. What is the date of birth (don't scroll down until you have an answer)?

If you're having trouble, I've highlighted the month for you:

If you said 10 January, you would not be alone - because that is the date someone entered into the Grandma database. But you would not be right :-(

Take a closer look at the image below where I've highlighted the date information:

The words underlined in green are the day. The Germans reads "d. ,31, ein und dreÿßigsten" which means "the 31st one and thirty." In other words the day was written first as a number and then in words. (Remember that German reverses the unit and the tens when writing out or speaking numbers.) You'll also notice that thirty is not spelled the modern way - this record has "dreÿßig" but it would be "dreißig" in modern spelling.

The red underlined word is the month, "Januar," or January.

Finally the blue underlined words are the time, ",10, zehn Uhr Ab.," or "10 ten o'clock in the evening." "Ab." is an abbreviation for "Abend" or evening.

So the date is not 10 January. We do it all the time, myself included, but it's awfully risky to make assumptions about what something says if you can't read (or don't take the time to read) all the words. Her birth date was 31 January 1813 at 10pm.

If you got it right, give yourself a big, gold star!

| ||

| Susanna Sudermann birth #2, XX XXXXXX 1819, Register of Mennonite births, marriages, and deaths 1813-1903, Neuteich Lutheran church records, Neuteich, West Prussia, no page, FHL film #208236. |

If you said 10 January, you would not be alone - because that is the date someone entered into the Grandma database. But you would not be right :-(

Take a closer look at the image below where I've highlighted the date information:

The words underlined in green are the day. The Germans reads "d. ,31, ein und dreÿßigsten" which means "the 31st one and thirty." In other words the day was written first as a number and then in words. (Remember that German reverses the unit and the tens when writing out or speaking numbers.) You'll also notice that thirty is not spelled the modern way - this record has "dreÿßig" but it would be "dreißig" in modern spelling.

The red underlined word is the month, "Januar," or January.

Finally the blue underlined words are the time, ",10, zehn Uhr Ab.," or "10 ten o'clock in the evening." "Ab." is an abbreviation for "Abend" or evening.

So the date is not 10 January. We do it all the time, myself included, but it's awfully risky to make assumptions about what something says if you can't read (or don't take the time to read) all the words. Her birth date was 31 January 1813 at 10pm.

If you got it right, give yourself a big, gold star!

Friday, January 6, 2017

Should You Mark That Grave?

I've been involved in putting a permanent marker at the poorly marked grave sites of three ancestors. While I've felt it was important to do it, I've also had a few qualms. I've wondered how sure I am that they were buried at the indicated location. The evidence might be questioned, even though I did my best to find the correct location. But I felt it was important to mark the grave both to make sure that what I had learned about their burial location was not lost and most importantly to commemorate the impact of their godly legacy on my life.

Here is one example: Johann Sudermann #26667 (1817-1907) died near Gotebo, Oklahoma. His obituary from Mennonitische Rundschau confirmed that he died there. According to my aunt, he was buried in the Gotebo Mennonite Brethren church cemetery. When that church closed in the 1910s, all their graves were moved to the Gotebo town cemetery. I checked FindAGrave and found his name listed in the Gotebo town cemetery but with no photo I put out a photo request, and a volunteer kindly offered to do it but replied that there was no such tombstone in that cemetery.

My aunt and I went to the Gotebo town office to ask for information, and they gave us a cemetery register that showed an unmarked grave ("grave here" in the image below) in the Suderman plot at the cemetery. She had been told by older relatives, now deceased, that that was Johann Sudermann's grave. The Aster Wiebe buried in the plot was Johann's great-granddaughter who died at Gotebo in 1911, so it all made sense.

But there was no written confirmation - only what my aunt had been told by older relatives. However, since my aunt is a careful genealogist, I felt that her information was reliable. We went to nearby Clinton, Oklahoma, and purchased a granite marker to be put on the grave. Maybe we made a bit of of a leap, but I'm glad that we put up the monument because otherwise my aunt's knowledge, even though it was not direct knowledge, would soon be lost forever.

Here's the new marker that we put up:

If you know of ancestors' graves that are unmarked or poorly marked, I encourage you to do something to make their memory more lasting. First, do your research to make sure that you are really marking your ancestor's grave. Ask older relatives what they know. Then go to FindAGrave and BillionGraves and upload photos of what is in place. If you have a blog, post what you know online. If you can afford it, get a granite marker with engraved (not raised) lettering to put on the site. Or even a metal plaque pressed into concrete is better than nothing. Other descendants may be willing to help with the cost, especially if you share some of your research that you have done, some of the stories that you have found, to make your ancestor come alive to them.

Here is one example: Johann Sudermann #26667 (1817-1907) died near Gotebo, Oklahoma. His obituary from Mennonitische Rundschau confirmed that he died there. According to my aunt, he was buried in the Gotebo Mennonite Brethren church cemetery. When that church closed in the 1910s, all their graves were moved to the Gotebo town cemetery. I checked FindAGrave and found his name listed in the Gotebo town cemetery but with no photo I put out a photo request, and a volunteer kindly offered to do it but replied that there was no such tombstone in that cemetery.

My aunt and I went to the Gotebo town office to ask for information, and they gave us a cemetery register that showed an unmarked grave ("grave here" in the image below) in the Suderman plot at the cemetery. She had been told by older relatives, now deceased, that that was Johann Sudermann's grave. The Aster Wiebe buried in the plot was Johann's great-granddaughter who died at Gotebo in 1911, so it all made sense.

|

| Suderman family plot, Plot #10 West half, Cemetery register book, Gotebo City Hall, Gotebo, Oklahoma. |

Here's the new marker that we put up:

|

| Johann Suderman tombstone, Gotebo City Cemetery, Gotebo, Oklahoma, 1 mile east of Gotebo on Highway 9, south side of road, plot #10. Photograph by Viola (Fast) Funk on 13 September 2013. |

Wednesday, January 4, 2017

Main Sources for Each Country

What are the main sources for each country where Mennonites have lived? If you're just getting into Mennonite genealogy, these might be the places to start looking. So in reverse chronological order:

Canada and United States

1. Family stories from older relatives

2. State/provincial vital records

3. Federal and state/provincial censuses

4. Land deeds and probate files

5. Mennonite church books

6. Diaries and letters

7. Passenger manifests for immigration

Russia/Soviet Union

1. EWZ records - German World War II family trees and life histories of Germans in occupied countries

2. Molotschna school records

3. Censuses

4. Newspapers - Mennonitische Rundschau and others were a main form of communication between Russia and North America

5. Diaries and letters

6. Archival materials from Odessa and other state archives

7. Immigration records from Prussia

Poland and Prussia

1. Mennonite church books

2. Lutheran and Catholic church books - many Mennonite vital records were recorded in these for various reasons

3. Censuses

4. Land records

5. Emigration records to Russia

Netherlands - I don't know much about researching these

1. Dutch Mennonite church archives

2. ???

Latin America and Germany are postwar destinations for Mennonites that also deserve some mention, but I know little about those.

Canada and United States

1. Family stories from older relatives

2. State/provincial vital records

3. Federal and state/provincial censuses

4. Land deeds and probate files

5. Mennonite church books

6. Diaries and letters

7. Passenger manifests for immigration

Russia/Soviet Union

1. EWZ records - German World War II family trees and life histories of Germans in occupied countries

2. Molotschna school records

3. Censuses

4. Newspapers - Mennonitische Rundschau and others were a main form of communication between Russia and North America

5. Diaries and letters

6. Archival materials from Odessa and other state archives

7. Immigration records from Prussia

Poland and Prussia

1. Mennonite church books

2. Lutheran and Catholic church books - many Mennonite vital records were recorded in these for various reasons

3. Censuses

4. Land records

5. Emigration records to Russia

Netherlands - I don't know much about researching these

1. Dutch Mennonite church archives

2. ???

Latin America and Germany are postwar destinations for Mennonites that also deserve some mention, but I know little about those.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)