NB: Somehow I published this post before it was finished. This is the final version.

In the finding guide for the Odessa, Ukraine State Archives, Fund 6, Inventory 2, I came across a record for a Penner living in the village of Prangenau in Molotscha Colony in 1847 who suffered damage in a hail storm. The damage must have been quite severe because the colony made a collection for him and several other families. Here's the bit of the finding guide:

Very interesting - my 3-greats-grandfather Jacob Penner #101378 (1777-1856?) lived in Prangenau village. Could he be the same Penner who suffered the hail damage and for whom the village made a collection?

A couple weeks ago I went to the Tabor College Center for Mennonite Brethren Studies and scanned the relevant pages from the file. Just yesterday I got around to looking at them, and the Penner affected by the hail storm was Jacob It matched! The microfilm quality is awful but take a look:

1835 Molotschna census index to see if there were any other Penners in Prangenau - it's always possible there was another Jacob Penner or two in the same village. In fact, there were three Penner families in Prangenau in the 1835 census. One was my ancestor Jacob Penner at Prangenau #15; another was his son Jacob, also living at Prangenau #15; and the third was a Peter Penner #281611, whom I suspect is a cousin but don't know for sure. (Importantly, according to Grandma, this third Peter Penner had no son named Jacob, so I can be sure the Jacob Penner who suffered from the hailstorm is not a son of Peter.)

In the 1847 election lists from Molotschna, which is of landowners only, there are two Penners, Jacob and Peter in Prangenau. Good news - there is no extra Jacob Penner in the village, at least among the landowners. It is always possible that Jacob's son Jacob had taken over the farm and that this was not my 3-greats-grandfather but his son, who was not my direct ancestor. But I think this is unlikely because there is a family memoir that says the older Jacob Penner lived until 1850 or 1856.

In the 1850 voting for the doctor that I recently extracted, there are two Penners, the same Peter Penner and a Franz Penner, who is my 2-greats-grandfather and son of Jacob Penner. It appears that in 1847, father Jacob Penner still ran the farm but that by 1850, he had turned it over to his son Franz.

All good news so far - there is only one Jacob Penner in the village and he is my 3-greats grandfather, so the file is of interest to me.

Now the bad news - I CAN'T READ IT! The microfilm is so bad that I can't make out more than a few words. Next week I want to go back to CMBS and see if I can focus the scanner better. Or maybe I can read it directly on the screen, even if a scan is not of sufficient quality to read. But I have to go back because I really want to know about the hailstorm that my great-great-great-grandfather suffered and the help that the colony gave him to recover. I'm not giving up yet.

Thursday, March 30, 2017

Monday, March 20, 2017

Hamburg vs. North American Passenger Lists

Whenever our Mennonite ancestors departed a European port, a passenger manifest was prepared before they left and filed at the port. Unfortunately, most of those have been destroyed, but lists for Hamburg for 1850-1934 and Bremen 1904-1914 have survived. Since the vast majority of Mennonites departed from Hamburg, this is a resource not to be missed.

The Hamburg lists (and possibly the Bremen lists, although I have not used them) are better than the North American lists for several reasons. Generally, the handwriting is better on the Hamburg lists. The Hamburg clerk spoke German, so he could communicate better with the emigrants than the New York clerk. And the Hamburg list usually gives more detail on the geographic origin of the passenger, usually giving the province (not just the country as the New York lists do) and sometimes even giving the exact village name.

The best way to find the Hamburg list is to search on Ancestry.com. To go directly to the collection, this is the link. If you don't have an Ancestry subscription, you have to order the microfilm from the Family History Library. If anyone knows of a free source, please add that in a comment.

If you can't find your ancestor's name in the Ancestry index to the Hamburg lists, you can search them manually for the ship and then go through that ship's passenger manifest. The typical transatlantic voyage took about two weeks, so start 3-4 weeks before they arrived in North America and go forward until you find the ship.

Here's an example of the illegible chicken scratches on a typical Quebec arrival record (and this is not the worst by far):

Which would you rather try to read?

The best way to find the Hamburg list is to search on Ancestry.com. To go directly to the collection, this is the link. If you don't have an Ancestry subscription, you have to order the microfilm from the Family History Library. If anyone knows of a free source, please add that in a comment.

If you can't find your ancestor's name in the Ancestry index to the Hamburg lists, you can search them manually for the ship and then go through that ship's passenger manifest. The typical transatlantic voyage took about two weeks, so start 3-4 weeks before they arrived in North America and go forward until you find the ship.

Here's an example of the illegible chicken scratches on a typical Quebec arrival record (and this is not the worst by far):

er er |

| Passenger Manifest of Vessels Departing Hamburg, Germany, 7 August 1874, ship Halifax, lines 62-64, Hamburg Passenger Lists 1850-1934, Staatsarchiv Hamburg, Germany, Indirekt Band 26, Microfilm S_13127. Accessed at Ancestry.com on 23 November 2013. |

Update on Elisabeth (Fast) Sudermann's Missing Grave

Here's an update to my recent (by now not-so-recent) post on Elisabeth (Fast) Sudermann's grave. After not finding her grave in Greenwood Cemetery in Newton, Kansas, I sent an e-mail to First Mennonite Church in Newton, Kansas, to ask if they had any information about her since she was living with her children who were members there when she died.

Within hours I had a response from a member of the church's historical committee. He invited me to come to the Harvey County Historical Museum that evening to use some of their resources to search for her grave. They are housed in the old Carnegie Library, a beautiful building which is worth a visit simply on its own. He had a lot of suggestions - none of which have panned out yet - but they are all good ideas worth sharing with you, dear reader.

Local Newspaper. I had found three different obituaries or mentions of her death in Mennonite newspapers, but I hadn't looked in the local newspaper, the Newton Daily Kansan. I searched for about a week after her death and didn't find any mention. Although it didn't work this time, it makes sense that a local newspaper might have burial details when an international Mennonite newspaper doesn't. But I did find a notice of a lawsuit when a lender sued her husband, Johann Sudermann, for defaulting on a loan.

Old Plat Maps. I wondered if she might have been buried on her children's farm, so he showed me a couple plat maps, and there were no cemeteries or burials marked on the maps in that area. But their ownership was not marked on any of the plat maps, so I wasn't sure if I was looking in the right place.

Contact the FindAGrave Contributor. I contacted Tom Crago, who manages all of the late Adalbert Goertz' thousands of uploads to FindAGrave. Unfortunately, he was unable to give me any more information, but he did transfer the memorial to me, so I added a note that the grave was not at the location indicated.

Local Cemetery Listings. The Historical Museum has transcribed the tombstones in many (but not all) Harvey County cemeteries, but Elisabeth Fast's grave was not mentioned in any of them. I also went online to the Reno County Genealogical Society's cemetery listings (the Mennonite community spilled across the county line into Reno), but I didn't find anything there.

Farm Burial. In the early days of settlement, many people were buried at their farms. Many of these burials have been lost because they were never well marked. And some farmers sadly would rather grow an extra bushel of wheat than preserve a burial plot, so some have been plowed over. Since Elisabeth Fast was living with her children east of Newton when she died, I want to locate their farm in the county land records and then go to the farm to see if there is a sign of a burial plot there. But I haven't done that yet.

While none of the suggestions have panned out (at least yet), they were all good ones.

Within hours I had a response from a member of the church's historical committee. He invited me to come to the Harvey County Historical Museum that evening to use some of their resources to search for her grave. They are housed in the old Carnegie Library, a beautiful building which is worth a visit simply on its own. He had a lot of suggestions - none of which have panned out yet - but they are all good ideas worth sharing with you, dear reader.

Local Newspaper. I had found three different obituaries or mentions of her death in Mennonite newspapers, but I hadn't looked in the local newspaper, the Newton Daily Kansan. I searched for about a week after her death and didn't find any mention. Although it didn't work this time, it makes sense that a local newspaper might have burial details when an international Mennonite newspaper doesn't. But I did find a notice of a lawsuit when a lender sued her husband, Johann Sudermann, for defaulting on a loan.

Old Plat Maps. I wondered if she might have been buried on her children's farm, so he showed me a couple plat maps, and there were no cemeteries or burials marked on the maps in that area. But their ownership was not marked on any of the plat maps, so I wasn't sure if I was looking in the right place.

Contact the FindAGrave Contributor. I contacted Tom Crago, who manages all of the late Adalbert Goertz' thousands of uploads to FindAGrave. Unfortunately, he was unable to give me any more information, but he did transfer the memorial to me, so I added a note that the grave was not at the location indicated.

Local Cemetery Listings. The Historical Museum has transcribed the tombstones in many (but not all) Harvey County cemeteries, but Elisabeth Fast's grave was not mentioned in any of them. I also went online to the Reno County Genealogical Society's cemetery listings (the Mennonite community spilled across the county line into Reno), but I didn't find anything there.

Farm Burial. In the early days of settlement, many people were buried at their farms. Many of these burials have been lost because they were never well marked. And some farmers sadly would rather grow an extra bushel of wheat than preserve a burial plot, so some have been plowed over. Since Elisabeth Fast was living with her children east of Newton when she died, I want to locate their farm in the county land records and then go to the farm to see if there is a sign of a burial plot there. But I haven't done that yet.

While none of the suggestions have panned out (at least yet), they were all good ones.

Sunday, March 19, 2017

The First Question

I am certain that you, dear reader, had a burning question after reading yesterday's post on the voting lists of Molotschna colony. You would have wanted to know how you too could access the genealogical treasures found in the Odessa Archives. And now I am going to answer that question for you.

Soviet archivists prepared a finding guide containing the description of every file, and someone has translated them into English and/or German. These finding guides are hosted online by the Mennonite Heritage Centre in Winnipeg with one guide for each "inventory."

Now a word about Soviet archival practice. The materials at a Soviet archive are grouped into fondy, which is usually translated "fund" or "fond," which gathers similar materials together. The fond that I used from the Odessa Archive is #6, which I believe is the records of the Guardianship Board for Foreign Settlers, which oversaw the Mennonites and other foreign settlers in Russia. The fond is then divided into opisi, which is usually translated "inventory." The inventory that I used was #2. Finally, individual matters are in folders called dela, or "files." The voting list was in file #11792. So if I wanted to quickly identify this file, I would say "Odessa 6-2-11792."

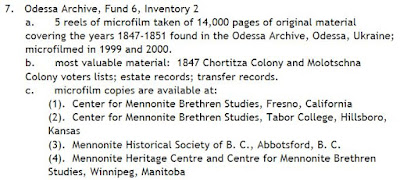

So how to access the files? You could go to Odessa, Ukraine, and visit the archive; but since that is not convenient for most of us, some wealthy Mennonites have generously paid to have the files microfilmed and deposited in archives in the US. You can find out where the microfilm of a particular set of documents may be viewed by going to Tim Janzen's website on Russian Mennonite genealogy, and scrolling down to Section R, Microfilm Collections. You would note the Fond 6, Inventory 2 is #7 on his list, and it may be found at Hillsboro, Fresno, Abbotsford, and Winnipeg. Since the Center for Mennonite Brethren Studies at Tabor College in Hillsboro, Kansas, is only a block away from my house, I dropped by for a visit.

How did I know what was interesting among the 14,000 pages of materials? I went through the finding guide line by line until I found this gem:

At left I underlined the archival file number 6-2-11792, and in the middle the date to which the documents relate are underlined. On the right I marked the phrase "Decisions of Mennonites' meetings with signatures of colonists." Along with the list of villages, this indicated that I would find the signatures of most or all of the landowners of Molotschna colony. I figured this would be similar to the valuable 1847 voters lists, and indeed it is.

When I go through the finding guides, I look for three categories of records. One is general lists, such as the one above, that have many Mennonites names in them. Usually I can find many ancestors in there. Second, I look for files about specific ancestors - for instance, I found the passport file for my 4-greats grandfather Johann Sudermann, who went back to Prussia in the 1840s to settle his father's inheritance. Finally, I look for more specific items that might mention my ancestors. For example, one file on my list to check is a list of those with contracts to herd sheep for the villages - I wonder if some of my non-landowning ancestors might have herded sheep to survive.

When you dive into the Odessa archival files, I would encourage you to start with inventory 1 because the finding guide is a searchable PDF (some of them are not searchable), in English, and nicely formatted. Make a list of all your direct ancestors who lived in Russia and their villages (if you know them) to help you as you search. Also remember that there is a lot of chaff to sort through in the finding guide, stuff that is not relevant to you. In a 30-page finding guide, you might only find 4-5 items that interest you, so don't give up too soon. Don't hesitate on this one - there are real treasures here that very few people know about.

Soviet archivists prepared a finding guide containing the description of every file, and someone has translated them into English and/or German. These finding guides are hosted online by the Mennonite Heritage Centre in Winnipeg with one guide for each "inventory."

Now a word about Soviet archival practice. The materials at a Soviet archive are grouped into fondy, which is usually translated "fund" or "fond," which gathers similar materials together. The fond that I used from the Odessa Archive is #6, which I believe is the records of the Guardianship Board for Foreign Settlers, which oversaw the Mennonites and other foreign settlers in Russia. The fond is then divided into opisi, which is usually translated "inventory." The inventory that I used was #2. Finally, individual matters are in folders called dela, or "files." The voting list was in file #11792. So if I wanted to quickly identify this file, I would say "Odessa 6-2-11792."

So how to access the files? You could go to Odessa, Ukraine, and visit the archive; but since that is not convenient for most of us, some wealthy Mennonites have generously paid to have the files microfilmed and deposited in archives in the US. You can find out where the microfilm of a particular set of documents may be viewed by going to Tim Janzen's website on Russian Mennonite genealogy, and scrolling down to Section R, Microfilm Collections. You would note the Fond 6, Inventory 2 is #7 on his list, and it may be found at Hillsboro, Fresno, Abbotsford, and Winnipeg. Since the Center for Mennonite Brethren Studies at Tabor College in Hillsboro, Kansas, is only a block away from my house, I dropped by for a visit.

How did I know what was interesting among the 14,000 pages of materials? I went through the finding guide line by line until I found this gem:

When I go through the finding guides, I look for three categories of records. One is general lists, such as the one above, that have many Mennonites names in them. Usually I can find many ancestors in there. Second, I look for files about specific ancestors - for instance, I found the passport file for my 4-greats grandfather Johann Sudermann, who went back to Prussia in the 1840s to settle his father's inheritance. Finally, I look for more specific items that might mention my ancestors. For example, one file on my list to check is a list of those with contracts to herd sheep for the villages - I wonder if some of my non-landowning ancestors might have herded sheep to survive.

When you dive into the Odessa archival files, I would encourage you to start with inventory 1 because the finding guide is a searchable PDF (some of them are not searchable), in English, and nicely formatted. Make a list of all your direct ancestors who lived in Russia and their villages (if you know them) to help you as you search. Also remember that there is a lot of chaff to sort through in the finding guide, stuff that is not relevant to you. In a 30-page finding guide, you might only find 4-5 items that interest you, so don't give up too soon. Don't hesitate on this one - there are real treasures here that very few people know about.

Saturday, March 18, 2017

Molotschna Voting List for 1850

In Molotschna Colony in Russia, the landowners had to vote frequently in the village assemblies on issues affecting the colony. Only the landowners could vote, so not every family is listed. And only the heads of households are listed. Some of these voting lists have been preserved in the various archives in Ukraine. Tim Janzen has extracted one of these here, the list for the voting for village and district mayors in 1847. These lists are valuable for genealogists because you can see whether your ancestor owned a farm, which tells you a lot about the family's economic status. And if your ancestor was a landowner, it gives you confirmation of his residence in a certain year.

I have been going through some microfilms at the Tabor College Center for Mennonite Brethren Studies in Hillsboro, Kansas, specifically the ones designated as Fond 6, Inventory 2; and I found a number of voting lists from the 1840s and 1850s. I decided to extract and post online the names from one that dealt with hiring a professional doctor for the Molotschna colony in 1850-1851. There are over 1200 names, so I'm kind of regretting my decision to do this, but I'm going to finish it anyway.

Here is the page with the names from the protocol for Margenau village reporting the voting for the doctor. They are even signed by the landowners, so this is a great way to collect signatures of your ancestors.

He was my great-great-grandfather. Interestingly, he is not in the 1847 voting list for Margenau that I mentioned above, so he must have gotten a farm and moved to the village between 1847 and 1850, when he would have been between ages 34 and 37. So this list adds some detail to his life. It also shows that he spent his 20s and early 30s landless, probably working as a farm laborer. Since he had five children by the time he moved to Margenau, he experienced poverty and the responsibility of providing for a growing family with only limited means as well as God's blessing in providing him with a farm. This shows how you can combine a bureaucratic document that has very little information in and of itself with other documents and facts to create a picture of a person's life.

I have been going through some microfilms at the Tabor College Center for Mennonite Brethren Studies in Hillsboro, Kansas, specifically the ones designated as Fond 6, Inventory 2; and I found a number of voting lists from the 1840s and 1850s. I decided to extract and post online the names from one that dealt with hiring a professional doctor for the Molotschna colony in 1850-1851. There are over 1200 names, so I'm kind of regretting my decision to do this, but I'm going to finish it anyway.

Here is the page with the names from the protocol for Margenau village reporting the voting for the doctor. They are even signed by the landowners, so this is a great way to collect signatures of your ancestors.

He was my great-great-grandfather. Interestingly, he is not in the 1847 voting list for Margenau that I mentioned above, so he must have gotten a farm and moved to the village between 1847 and 1850, when he would have been between ages 34 and 37. So this list adds some detail to his life. It also shows that he spent his 20s and early 30s landless, probably working as a farm laborer. Since he had five children by the time he moved to Margenau, he experienced poverty and the responsibility of providing for a growing family with only limited means as well as God's blessing in providing him with a farm. This shows how you can combine a bureaucratic document that has very little information in and of itself with other documents and facts to create a picture of a person's life.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)